by Dana Harris-Trovato

Award-winning poet and MacArthur Fellow Terrance Hayes graced the CityLit Festival: Reimagined Zoom stage as a featured event, in conjunction with the Enoch Pratt Free Library, on March 9, 2021. In his usual unassuming style, he chose not to read or talk about his own writing first, but instead presented an overview of Black women poets in the 20th century, particularly the works of poet, author, and teacher Gwendolyn Brooks.

Hayes brought Brooks to life, explaining her focus on elemental aspects of life — those seemingly simple everyday experiences that, in fact, are layered in complexity. Knowing the impact of hearing the poet firsthand, he shared recordings of her reciting her poems with her signature, inimitable sing-song rhythms. He identifies her as the original ‘air-bender’. His review of her life from 1917-2000 revealed her as a direct product of the Great Migration who helped establish Chicago as a foundation for poetry by memorializing life in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the city’s South Side. Any poetry in Chicago after 1945 exists only in her shadow.

Despite enormous success, and the fact that she was the first African-American to receive the Pulitzer Prize in 1950, Hayes expressed countless examples of how Brooks was often forgotten in her day and even now when talking about 20th century poetry. Even in poetry compiled by Black authors, such as in the anthology Black Fire, a documentation of the Black Arts Movement published in 1968, editor Amiri Baraka failed to include Brooks’ poetry (and the work of Audre Lorde and Lucille Clifton.)

Hayes continued to explain the rich and extensive work of many of Brooks’ contemporaries, including Mari Evans (1919-2017), Sonya Sanchez (1934-), Audre Lorde (1934-1992), Lucille Clifton (1936-2010), Barbara Chase-Riboud (1939-), and the Chicago born poets Patricia Smith (1955-) and Krista Franklin (birthdate unknown).

Patricia Smith’s poem “Black Poured Directly Into the Wound” (Incendiary Art, 2017) is in response to Brooks poem “The Last Quatrain of the Ballad of Emmett Till” (from The Bean Eaters, 1960), where Smith expounds on Brooks’ depiction of Till’s mother, after the murder and after the burial, imagining the unimaginable:

“Mamie, she of the hollowed womb, is nobody’s mama anymore…Faced with days and days of no him…Is this how the face slap of sorrow changes the shape of a mother?”

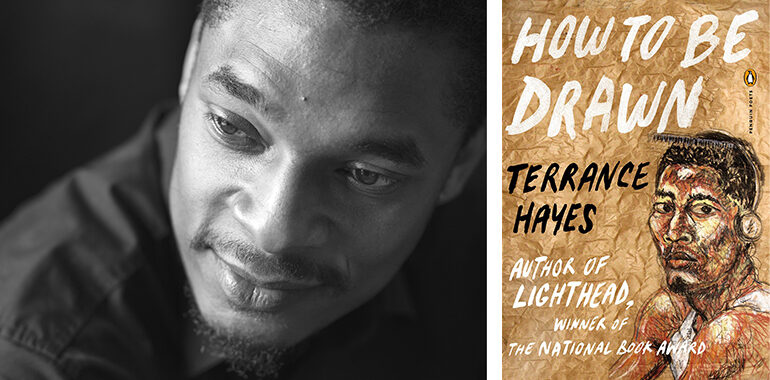

Although Hayes is reluctant to talk about his own work, he is a longtime lover of playing with poetic forms. Not only has he written a book of sonnets (American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassins) but he also created the poetic form called the Golden Shovel, whereby the last words of each line in a poem are, in order, words from a line or lines taken from another poem. The poems are, in a way, secretly encoded to enable both a horizontal reading of the new poem and vertical reading down the right-hand margin of an original. He described how this is done with Brooks’ poems in The Golden Shovel Anthology: New Poems Honoring Gwendolyn Brooks edited by Patricia Smith, Peter Kahn, and Ravi Shankar, 2017.

In speaking with Clint Smith, poet, staff writer at The Atlantic, and author of the forthcoming How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning With the History of Slavery Across America, Hayes explained how he was first introduced to the work of Gwendolyn Brooks in college when he heard someone recite the “The Mother”. It is a poem that illustrates her strong feminist poetics as early as 1945. A pivotal moment, it moved him in a way like no other art form. As a result, he began a lifelong love of Brooks’ work and changed his major from visual art to poetry. He continues to paint and mentioned the strong impact art, music and basketball have made in his life, encouraging everyone to dabble in many art forms as there is power in how they inform each other.

In discussion of his own poetry, he alluded again to Brooks’ style of capturing everyday experiences, celebrations, and struggles. He emphasized how a poet doesn’t have to be an expert, but merely a ‘witness’, and how valuable that is to remember. Whether it’s witnessing the personal or political, it’s important to be attuned to what’s going on around you and be aware of how it affects you. In being witnesses, we are freed up to relay our world without the weight of authoritative knowledge. In light of 2020, years from now, people will ask where you were, what you did, and how the year affected your life.

Hayes also discussed what makes a poem move and what makes it moving? He challenged us to identify where the heat lies underneath? When creating or looking at a poem those two questions should always come to mind.

We were delighted to hear Terrance read his new poem, “Woolworth”, where he continued his playful expressions combining such words as ‘rapt’ with ‘wrapped’, introducing levity despite the difficult subject matter.

Terrance Hayes extended his time with us an additional half hour taking questions from writers in the CityLit Writer’s Room, a new, more intimate feature launched in this year’s virtual festival. In the discussion of how we have or haven’t survived the heaviness of 2020, he reminded us to ‘weather the storm’, as Brooks’ stated in the last line of her poem, “The Second Sermon on the Warpland” from In the Mecca, 1968:

“Conduct your blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind.”

Also, in the Warpland poem, we are introduced to the term ‘furious flower’ which was the inspiration for the Furious Flower Poetry Center at James Madison University (CityLit’s good friends and part of The CityLit Village). Founded by Joanne Gabbin, it is the nation’s first academic center devoted to Black poetry. From the poem:

“The time

cracks into furious flower. Lifts its face

all unashamed. And sways in wicked grace.”

Read the entire poem here.

Thank you, Terrance Hayes, for your generous, instructive time with us. Your attention to the work of outstanding Black women poets and their great contribution to your life and ours was encouraging and noteworthy.

DANA HARRIS-TROVATO, CityLit Board Chair, is a fiction writer who has been professionally involved in managing nonprofits for over 25 years. In 2020, she received her MFA in Creative Writing from St. Francis College in Brooklyn, NY, where she completed her first novel and is currently an Adjunct Writing Professor.